Our purpose and strategy

Our purpose is Helping Britain Prosper.

The number of people experiencing homelessness in the UK is at an all-time high, with 240,000 households living in unsuitable temporary accommodation.

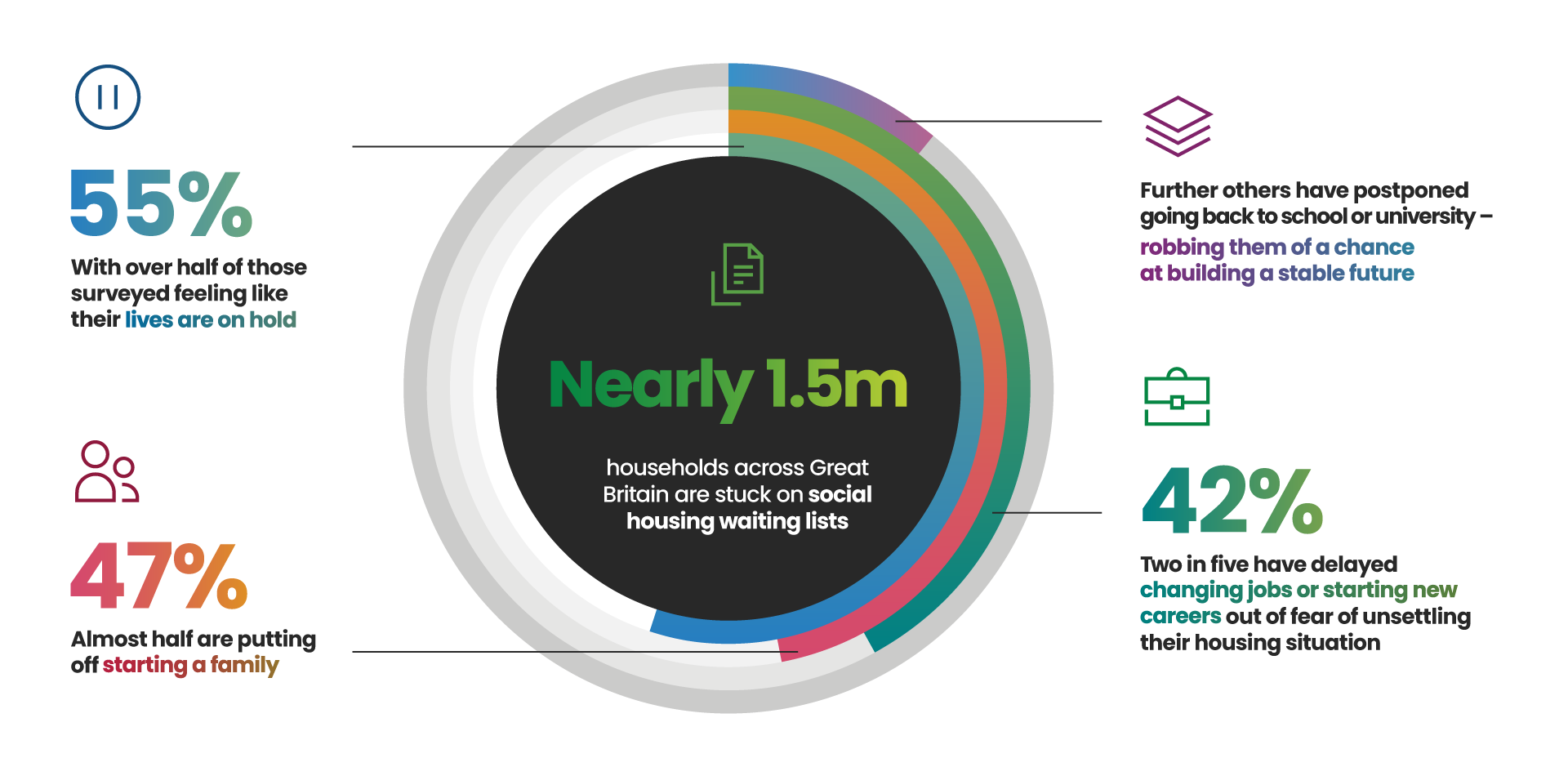

The UK is facing a housing crisis. With over 1.5 million households across the country stuck on social housing waiting lists we simply do not have enough homes. In some places, waiting lists for social housing can stretch to 55 years1. Without the security and stability of a social home, many households are forced into the insecurity of the private rented sector and the very real threat of eviction and homelessness.

The reality of experiencing homelessness is varied, impacting people and families in different ways. Homelessness can often be people who are sofa surfing, staying with friends or family, being housed in a hotel or bed and breakfast, or even sleeping somewhere as precarious as a garden shed or car. For those experiencing homelessness, many report dealing with issues such as overcrowding, with extended families living together, having to sleep on the floor or being trapped in one small room in temporary accommodation.

It cannot be understated how experiencing housing insecurity impacts people’s physical, mental and emotional wellbeing. Together with national homelessness charity Crisis, we’ve undertaken research into how the shortage of social housing is impacting people’s lives. The results are striking. Over half (55%) of those surveyed felt like their lives were on hold. Almost half (47%) said they are putting off starting a family and two in five (42%) have delayed changing jobs or starting new careers out of fear of unsettling their housing situation further.

For children, the effects of poor housing can be even more troubling. In England, over 150,000 children are currently living in temporary accommodation such as hostels, hotels and bed and breakfasts. This is equivalent to circa 5,000 school classrooms of children who cannot have friends over to play, a quiet area to study and often their own bed to sleep in.

Research by Shelter shows that 86% of teachers say that children have missed school as a result of homelessness or housing problems. They are less likely to achieve the grades required to go on to university and over the course of their lives they will go on to earn less.

We also know that experiencing homelessness can make work more challenging. For instance, one Crisis member recently shared that they had to walk two hours to work in the morning every day and then two hours back in the evening. Previous research from Crisis found that many were going to work after a disrupted night’s sleep or lacked access to the kind of daily facilities and amenities most of us take for granted, like the ability to wash their clothes or cook meals.

In the worst cases, they heard from members who have been dismissed when their living situation came to light.

Ending homelessness for good benefits everyone. For example, by building more social housing, we can support long-term employment prospects, providing people with certainty and security. Providing homes for 30,000 homeless people would mean an extra 6,500 people in work, if the employment gap between experiencing homelessness and having a secure home was closed by half.

The UK economy would also see an increase in employment from the construction of more social homes. House building supports between 4.1 and 4.5 full time employment jobs per house constructed, and for every construction job, a further 1.7 jobs are supported in the wider economy.2 More than half of any government subsidy for social housing could be recovered through increased tax receipts.

In addition, a report by the National Housing Federation demonstrates that building 90,000 social homes would return £37.8 billion to the economy within three years. It would also result in huge savings for the taxpayer, including £4.5 billion in savings from housing benefit, £3.3 billion of savings from Universal Credit, and £5.2 billion savings to the NHS.3

Our whitepaper looks all the way back to the post-WWII approach to housing provision; through the rapid growth in national housebuilding between the 1940s and 1970s (with a third of people renting from local authorities by the end of this period); to the state of the social housing landscape today.

Social housing offers residents security in terms of housing affordability and longevity. Once someone is given access to a social home, they are usually granted an assured tenancy - giving them more stability and the opportunity to have a safe and secure home.

However, waiting list times are at an all-time high, especially in London, and people can be in temporary accommodation for years before a social home will become available. For example, the waiting list in Lambeth is over 25,000 households4, and it can take up to 11 years to get a two bedroom home.5

For local authorities it would be far more cost effective in both the short and longer term to be able to house people in appropriate social housing. This would result in better outcomes for the individuals (greater security and better empowerment prospects), for children (being able to do their homework, have a place to play and more likely to lead to better grade outcomes and qualifications), and for local services in the authority.

For example, we’d expect families in stable and secure housing to reduce their GP visits, and be able to contribute more to the community by supporting local businesses like shops and pubs.

With more than 100,000 households in temporary accommodation, which includes more than 74,000 households with children, the need for safe, secure homes where they’re able to thrive, build a life and become part of a community has never been greater.

The Government’s ambition to deliver 1.5 million homes across this Parliament is welcome, but also represents a significant policy challenge across all types of tenure. We stand ready to work with the government and other stakeholders across the sector to deliver the homes the country needs.

Social housing undoubtedly plays a huge role in ending homelessness in the UK, which is why, alongside Crisis, we’re calling for one million more homes at social rent over the next decade. Only through the creation of more homes will we be able to end homelessness in the UK.

Managing Director & Head of Housing

David is a Managing Director with responsibility for Lloyds Banking Group’s relationships with clients in the house building and social housing sectors. Having joined Lloyds Bank in 1989, David undertook numerous roles across Retail and Commercial Banking before joining the Capital Markets division in 2000. David was instrumental in the development of the Bank’s Capital Markets business in both the public and private debt markets in the UK, USA and Europe. In January 2017, David returned to relationship banking to create a new team with responsibility for UK Housing.

David has a passion for sustainability and in 2021 became a Board director of Sustainability for Housing Ltd and joined the Executive Committee of NextGeneration, both of which focus upon developing sustainability reporting standards and frameworks in the rental and new build markets. He also supports Regeneration Brainery which focuses on the putting the S in ESG.

David is ACIB qualified and has a first class honours degree in Financial Services from The University of Manchester.

We’re launching new support to get more first-time buyers onto the property ladder.

Following our call alongside Crisis for one million more homes for social rent in the next decade, we answer some of the most prevalent questions about social housing and the role it plays in the UK housing market.

Helping people access affordable, quality and sustainable homes is an important part of our purpose of Helping Britain Prosper.

Popular topics you might be interested in

Sustainability Diversity Supporting business Housing Pensions Investment